The last female Ten’nō of Nara Japan

The Asuka and Nara periods of Japan witnessed five women who assumed the throne in their own right between 592 and 770, of whom two ruled twice under differing names. The last in this line of female succession was Kōken-Shōtoku Ten’no (‘Heavenly Soverign’). Her rule is perhaps one of the most controversial, due to the rise of Confucian politics and the legacy of her friendship with the Buddhist monk, Dōkyō.

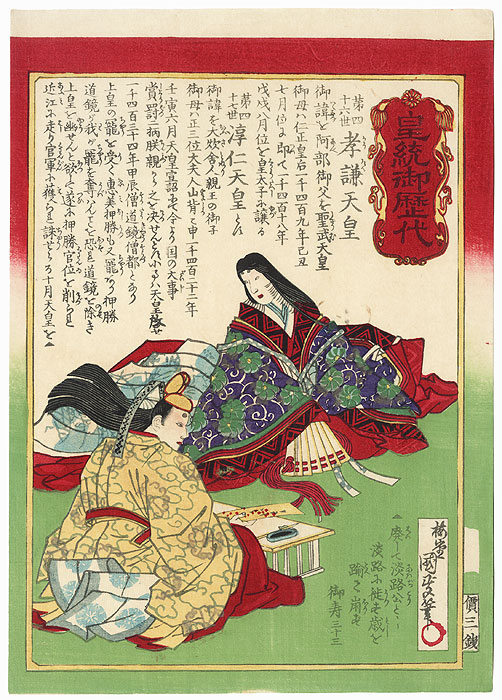

Born Abe to Shōmu Ten’no 天王 (r. 724-749) and Kōmyō Kōgō 皇后 (‘Empress’). Kōken-Shōtoku would be the royal couple’s only daughter and would become the heir to the Japanese throne. When Shōmu ascended to the throne, the court was divided, and much of his reign was devoted to reunifying the kingdom under the imperial seat. But by 749, the strain of rulership for the successful Ten’no and diminishing health led to his abdication in favour of his daughter.

The reign of Kōken Ten’no (r. 749-758)

When Kōken assumed the throne in 749, the kingdom she had inherited was far more united than it had been for her father’s accession. Her first reign aimed to consolidate both her own assumption of the crown and her parents’ legacy. Kōken had inherited both her parents’ devotion to the Buddhist faith, and Kōmyō became the best-known imperial consort for her religious devotion and social welfare work.1 Additionally, Shōmu and Kōken-Shōtoku pulled on the image of the Vairocana at Tōdai-ji Temple. Whilst construction of Todai-ji began at the zenith of Shōmu’s reign, its completion did not occur until his daughters. For Shōmu it represented his long struggle to unite his kingdom, which had been politically fractured since his ascension to power.2 In contrast, for Kōken-Shōtoku, it represented her devotion to her father’s ambition and a defence to not only her original ascension to the throne, but also when she returned a second time. However, in 758, the minister of state, Fujiwara Nakamaro convinced Kōken to abdicate in favour of her third cousin Jummin (r. 758-764). As a result of her abdication, Nakamaro was able to exert his influence over the crown. Not long after, Kōken fell ill; during this period, she met the Buddhist priest Dōkyō (in 761) who restored her to health.3

The reign of Shōtoku Ten’nō (r. 764-770)

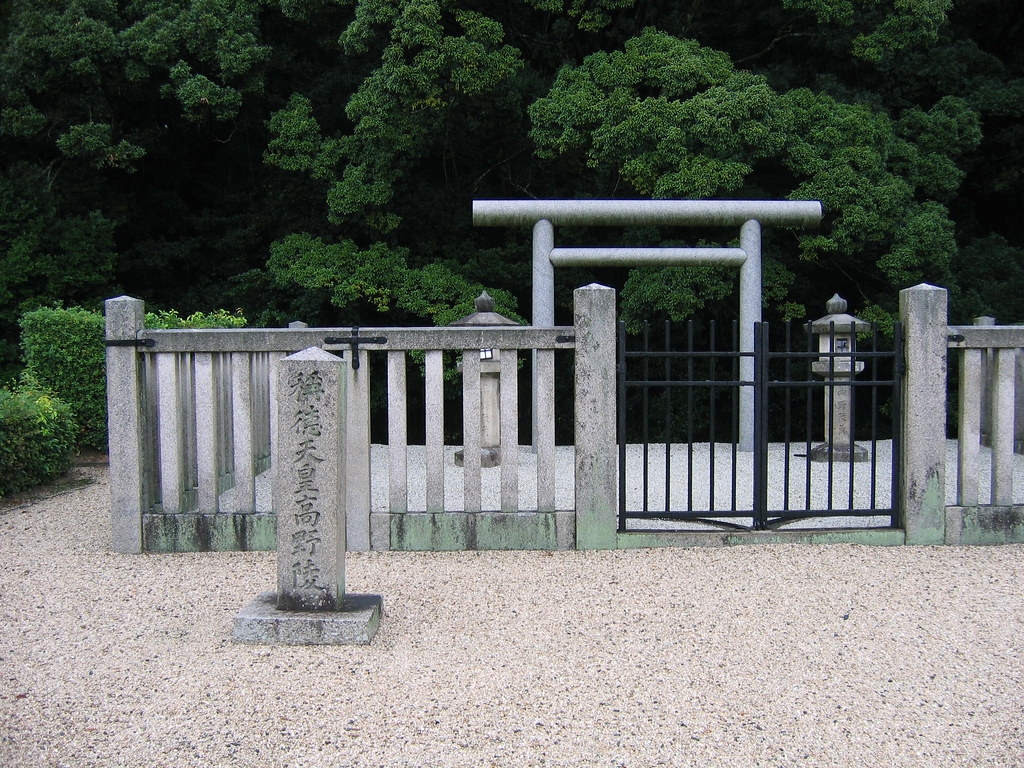

As a result of her return to health, she became more politically active, and by 763, she had grown tired of Jummin and so issued an edict sidelining his role as ruler, where she assumed all critical affairs of state. In 746, she overthrew Jummin and placed herself back on the throne as Shōtoku, which sparked a rebellion by Nakamaro, ending in his defeat. As a result of the rebellion and her return to power, to support her re-consolidation of her authority, she commissioned an enterprise of a million miniature pagodas, Hyakumantō Dhāranī (image to the left), which had never been achieved before or after her lifetime, for a more in-depth analysis refer to the footnotes.4 Many historians have challenged the assertion that her project ever reached the one million due to three core factors. Firstly, this enterprise is only mentioned in the Shōmu Ninhongi (one of six national histories of Japan); secondly, the printing required for such a number assumes that printing arrived in Japan centuries before China, and even before its confirmed use in Japan. Finally, the sheer volume, the total amount to be known, falls short of 50,000, a fraction of that declared in the chronicle to have been constructed.5 The enterprise stood as a reflection of divine support for her success and as a statement of her proposed rule, with the Dhāranī being sent to the Ten Great Temples across Japan, meaning each temple would have received 100,000 each. Furthermore, in 675, to match the construction of Tōdai-ji Temple by her father, she ordered the construction of the Saidai-ji Temple. The temple would solidify her claims as the true heir to her father’s throne when she overthrew Junnin Ten’nō in 764, based on being from the direct line of royal descent.

Omens

Another facet of Kōken-Shōtoku’s rulership was the use of omens to bolster her claim to the crown by divine sanction. As highlighted by historian Ross Bender, auspicious omens became an integral part of the development of royal political theology and legitimacy.6 During the reign of Kōken, six auspicious omens were reported, and twenty-one during Shōtoku’s, ranging from white animals, coloured clouds, gold and so on. These auspicious omens were used to validate and expand her authority and power during her second reign, reaching a form of zenith by the implied suggestion in Senmyō (edict) 42, of Japan being on the precipice of an era under the rulership of a great sage.7 Additionally, in Senmyō 14 and 45, give reference to either Shōmu Ten’nō, Kōmyo Kōgō (her mother and father) or Genshō Ten’no, the woman who moved the capital to Nara, sparking the Nara period.8 This was done to exhibit a continual and successive bloodline and descendants of rightful rule; by pulling on these individuals, the successor would foster a culture of association with previous power and thus secure their own.

The Dōkyō Incident

The ground of Kōken-Shōtoku and Dōkyō’s relationship has been questioned for much of history, with Confucian scholars arguing that they were romantically involved, while contemporary historians have argued that there is no ground in such assertions.9 But what is clear is that the years of Shōtoku’s reign witnessed Dōkyō’s climb to supreme power, holding the office of Daijō Daijun Zenji (the highest bureaucratic office), his control over the court, which witnessed the fall of many old noble families, and ultimately over the crown itself.10 It has been highlighted that near the end of Shōtoku’s reign, she was more than prepared to surrender the throne to him, but strong opposition ensured that she held onto the throne till her death in 770. Whilst in power, Dōkyō significantly influenced Shōtoku’s religious enterprise, ensuring the development and expansion of the Buddhist Temple Kokubunniji and the impressive Saidai-ji Temple.11

Legacy

However, when Kōken-Shōtoku fell ill and subsequently died in 770, Dōkyō quickly lost power at court and was removed. Her enterprise of the Hyakumantō Dhāranī was deemed a failure and waste, by a woman who had been misguided by her monk ‘lover.’ She was also criticised for enabling the disastrous policies of Dōkyō, and was used as the justification by which to bar further female rule in Japan, only seeing a brief return in the reigns of Meishō (r. 1629-1643) and Go-Sakuramachi (r. 1762-1770).

Footnotes:

- Michijo Y. Akio, “Jitō Tennō: The Female Soverign,” in Heroic with Grace: Legendary Women of Japan, ed by Chieko Irie Mulhern (Oxon: Routledge, 1991): 70. ↩︎

- Joan R. Piggott, The Emergence of Japanese Kingship (Redwood: Stanford University Press, 1997), 239 and 276. ↩︎

- Ross Bender, “The Hachiman Cult and the Dōkyō Incident,” Monumenta Nipponica 34, no. 2 (1979): 125. ↩︎

- Brian Hickman, “A Note on the Hyakumantō Dhāranī,” Monumenta Nipponica 30, No. 1 (1975): 87-93; Peter Kornicki, “Empress Shōtoku as a Sponsor of Printing,” in Tibetan Printing: Comparison, Continuities,

and Change, ed Peter Kornicki, Hildegard Diemberger, and Franz-Karl Ehrhard (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 45-50; Peter Kornicki, “The Hyakumantō Darani and The Origins of Printing in Eighth Century Japan,” International Journal of Asian Studies 9, No. 1 (2012): 43-70; Mimi Hall Yiengpruksawan, “One Millionth of a Buddha: The ‘Hyakumantō Darani’ in the Scheide Library,” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 48, no. 3 (1987): 224–38. ↩︎ - Kornicki, “The Hyakumantō Darani,” 45. ↩︎

- Ross Bender, “Auspicious Omens in the Reign of the Last Empress of Nara Japan, 749-770,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40, No. 1 (2013): 48. ↩︎

- Jingo Keiun 1.8.16: Senmyō 42, Sep 13, 767 (p. 110-113), Bender, The Edicts of the Last Empress, 749-770.* ↩︎

- Tenpyō Shōhō 1.7.2: Senmyō 14, Aug 19, 749 (p.73-75) and Jingo Keiun 3.10.1: Senmyō 45, Nov 3, 769 (p. 118-123), in Bender, The Edicts of the Last Empress, 749-770.* ↩︎

- Ronald P. Toby, “Why Leave Nara?: Kampuchea and the Transfer of the Capital,” Monumenta Nipponica 40, no. 3 (1985): 342. ↩︎

- Bender, “The Hachiman Cult,” 140. ↩︎

- Bender, “The Hachiman Cult,” 140. ↩︎

*Ross Bender, ed and trans, The Edicts of the Last Empress, 749-770: A Translation from Shaku Ninhongi,” (Create Space Independent Publishing Platform, 2015).

For further resources, refer to the Comprehensive Bibliography.