‘In violation of the ethics of proper governance’1

At the dawn of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman Empire entered ‘the era of the sultanate of women,’ seeing a number of women take the reins of government.2 Such practices, by its contemporaries, were viewed as an abhorrent circumstance that the empire had fallen into and which many argued witnessed the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Yet, among the women was Valide Sultan Kösem (left image). Her years in authority between 1623-1651 saw her act as regent for her sons Murad IV (r. 1623-1640) and Ibrahim I (r. 1640-1648), and later her grandson Mehmed IV. Her time as Valide Sultan (mother of the ruling Sultan) was a time of power struggles and assassinations as she not only wrestled to keep her authority against her children but also the wider court that believed a woman had no place in the central administration of the Empire.

From Haseki to Valide Sultan

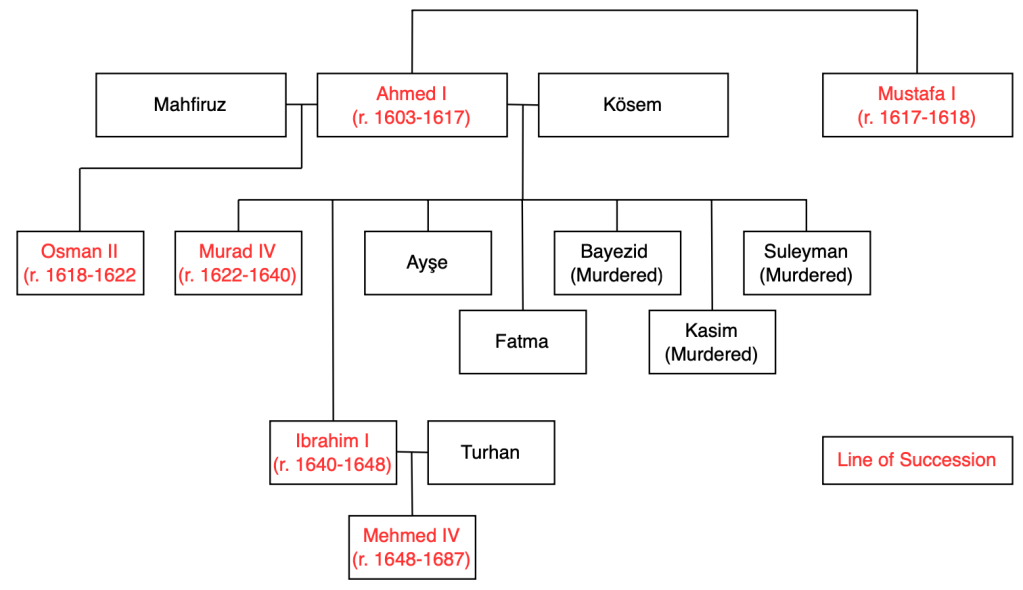

Kösem entered the harem of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617) as an Odalik (concubine), eventually rising to be a Haseki (chief consort of an Ottoman Sultan) and second wife. The practice of the concubinage system offered greater security to the succession of the dynasty. Still, it limited each concubine to birth only one son to ensure they nor their family could monopolise power over the crown. However, Kösem broke this tradition by having five sons with Ahmend, which resulted in her having considerable authority in court and influence over the line of succession.3 But upon Ahmed I’s death in 1617, Kösem was forced to support his brother Mustafa I (r. 1617-1618) to the throne. His reign would only last two months before he was overthrown and replaced by Ahmed’s son Osman II (r. 1618-1622). However, Osman was the son of a different concubine, Mahfiruz, resulting in Kösem being relegated to the old palace (Eski). She would remain here for several years until Osman II was deposed in 1622, and Kösem returned to court to see her son Murad IV ascend to the throne.

Sultan Murad IV (r. 1622-1640) to Sultan Ibrahim I (r. 1640-1648)

After Kösem’s return to power, she became the Valide Sultan and assumed a regency for her son Murad IV during his minority. Her exacting presence at court was complex, especially as it was common practice for the Grand Vizer to act as regent over the period when the Sultan was too young instead of his mother. Nonetheless, between 1622-1632, Kösem acted as head of state, whilst she simultaneously assembled a loyal household to ensure her hold on power remained. For example, as highlighted by Reneé Langlois, the harem in 1575 had a total of 49 women, but by 1633, due to Kösem in particular this number has increased to 433.4 When in 1633 Murad claimed the throne in his own right he had three of his four brothers murdered (Bayezid, Kasim and Suleyman). The final brother, Ibrahim, was protected by his mother in the harem – ensuring Murad could not get to him.

When Murad IV eventually died in 1640 with no heirs, Kösem’s early decision to save Ibrahim ensured that both the dynasty survived and her own hold on power continued. However, Ibrahim was mentally ill, earning the title ‘mad Ibrahim.’ As a result, Kösem assumed a second regency for her son. It was during this regency that she was awarded titles such as Buyuk Valide (the great Valide Sultan), ‘umm al-muminin (the mother of believers) and Sahibat al-makam (the possessor of Rank).5 She also issued orders of state on behalf of her son where her title as Valide Sultan appeared at the bottom. Even the Granz Vizer Sofu Mehmed Pasha addressed Kösem as Sultanim, devletlu efendin (my Sultan, your stately Excellency.6 All of her hard work from the death of her husband in 1617 till her second regency (1640-48) was finally demonstrated through her ability to exercise authority in such an outright form.

‘In the end, he will leave neither you nor me alive …’7

But, when Ibrahim had had enough of his mother’s influence, she was temporarily removed from the court. But the tides had already changed against the sickly sultan. With a deteriorating state of affairs and war in Venice in 1648, Kösem successfully deposed her second son and later had him strangled to death. In his place, she positioned her 7-year-old grandson, Ibrahim’s son Mehmed IV, on the throne. Kösem had inadvertently, by removing her son in favour of her grandson, started a motion in which she would not be the victor. It was expected that when a new generation of Sultans assumed power, their direct mothers would assume the role of Valide Sultan; in this case, Turhan (right image) should have replaced Kösem.8 But Kösem did not relinquish her power, with some at court viewing her seniority and guidance as an essential fabric of the palace and government. Between 1648 and 1651 the tensions between Turhan (as Junior Valide Sultan) and Kösem (as Valide Sultan) continued to worsen till Kösem attempted to assassinate her main rival for power. But, her plot was short-lived having been revealed to Turhan by none other than Meleki Hatun, one of Kösem’s own confidants, after he realised the tides had now turned against the old Valide Sultan.9 A month prior, Istanbul had erupted in rebellion against the Vizer, and the Harem itself was falling into political turmoil, and Kösem’s hold on power was slipping.10 Upon hearing the plot, Turhan devised a separate plot to remove Kösem, seeing in September 1651 the once powerful mother and grandmother strangled to death.

Legacy

Despite Kösem’s determination to hold onto power, removing her second son from power started the decline of her authority. But her legacy as a woman of charity and goodwill survived. As highlighted by court historian Naima, Kösem was praised for her commitment to free her female slaves after three years of service, and for during the months of Ramadan visiting prisons and paying off the fines and debts of prisoners so they could regain their freedoms.11 Similarly she is also noted for her charity towards pilgrims, offering food and clothes. Equally, at the Çinili Mosque in Üsküdar (left image), found at the entrance and courtyard portal remains an inscription referring to Kösem’s goodwill:

“Her exalted majesty the Valide Sultan always performed glorious acts of charity out of the sincere love of God. She built this congregational mosque and had its many estates endowed to support it.”12

She may have fallen from power after three decades of authority, but her legacy as a pious and charitable ruler and mother survived.

Footnotes:

- Fariba Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality, Crossing Gender and Communal Boundaries in an Age of Political Crisis and Religious Controversy,” in Living in the Ottoman Realm: Empire and Identity, 13th to 20th centuries, ed. Christine Isom-Verhaaren and Kent F. Schull (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016): 98. ↩︎

- Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality,” 98. ↩︎

- Reneé N. Langlois, “Power and Authority of Royal Queen Mothers: Juxtaposing the French Queen Regent and the Ottoman Validé Sultan During the Early Modern Period,” Masters of History, University of Nevada, 2018: 4. ↩︎

- Langlois, “Power and Authority of Royal Queen Mothers,” 60. ↩︎

- Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality,” 199. ↩︎

- Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality,” 199. ↩︎

- Langlois. “Power and Authority of Royal Queen Mothers.” 61. ↩︎

- Lucienne Thys-Şenocak, Ottoman Women Builders: The Architectural Patronage of Hadice Turhan Sultan (London: Routledge, 2016), 26. ↩︎

- Thys-Şenocak, Ottoman Women Builders, 27. ↩︎

- Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality,” 199. ↩︎

- Zarinebaf, “Policy Morality,” 201. ↩︎

- Thys-Şenocak, Ottoman Women Builders, 89. ↩︎

For further resources, refer to the Comprehensive Bibliography.