The real power behind the throne1

The dawn of the seventeenth century for the Mughal empire of India was plagued with a power struggle for the throne between the ailing Akbar emperator (r. 1556-1605), his son Jahangir (r. 1605-1627) and his grandson Khusrau (1587-1622). Akbar would eventually name Jahangir his successor, seeing him ascend to the throne in 1605. Jahangir’s reign, however, would be one addicted to drink and opium, seeing him willingly hand the power of the crown over to his last wife Nur Jahan. Her tenure in power saw her accumulate such authority that she became sole ruler in all but name.2 From astute politician to masterful manipulator, she held the reins of government for nearly two decades (1611-1627), which also oversaw an extensive array of architectural programs and extensive trade with the West. Yet her reign also bore witness to two rebellions (1622-1626 & 1626), the junta’s rise and fall, and her eventual fall from power in 1627.

From ‘Light of the Palace’ to ‘Light of the World.’3

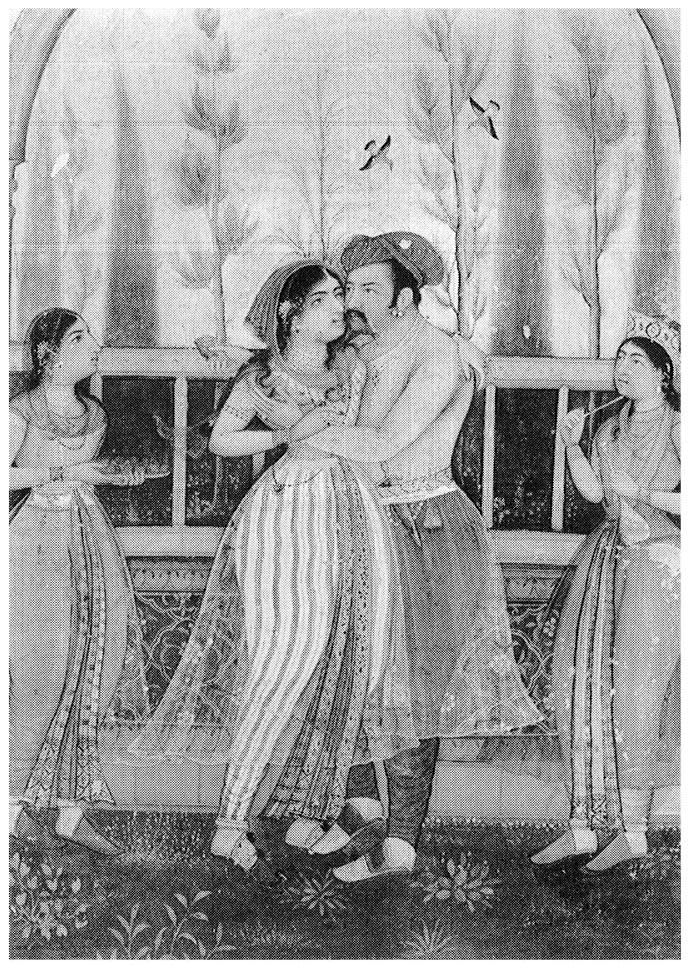

Born Mihrunnisa in 1577, Nur Jahan was the daughter of Itimaduddaula, a Persian aristocrat who ‘migrated’ to the Mughal Court and assumed the position as a courtier under the regime. In 1594, she was married to her first husband, a Persian adventurer, Ali Quli Khan Instajlu, but some thirteen years later, she would be left widowed with a daughter – Ladli Begam (1605-1677) – after her husband’s murder in 1607. As a result of her husband’s death, Nur Jahan was summoned to the Mughal court in Agra, where she became a handmaiden in the imperial harem.4 Between 1607 and 1611, little is known of what became of Nur Jahan’s life in the harem, apart from the fact that she was entrusted to Jahangir’s stepmother, Ruqayya Sultan Beham. Historians have questioned just quite when Jahangir and Nur Jahan first met. It is plausible, given her presence in the harem, that the two had made company before 1611. However, despite this, the first recorded proof of them meeting was at the palace Meena Bazaar during the festival of Nowruz in March 1611, where the two fell in love and married one another on May 25th, 1611. From that point onwards until her eventual fall in 1627, Nur Jahan steadily increased her power, reserved solely for the ruler. As highlighted by Abraham Eraly, ‘she seized the reins of government and arrogated to herself the supreme civil and financial administrator.’5 But this feat was not achieved alone, with her family – commonly now regarded as the junta (a military or political group that rules a country after taking power by force) – having played a crucial role in establishing an infrastructure that allowed them to gain, consolidate and apply their power and authority. Directly following Jahangir’s and Nur Jahan’s marriage, her father Itimaduddaula, was promoted to the rank of 1,800 zat, and then 2,500 zat and 500 suwar in 1611, with an additional gift of rs. 5,000.6 He rose to such a position that Jahangir valued his advice dearly and that he was perceived at court as a fair minster, despite the bribery that transpired. Her brother Abul Hasan received the title Itiqad Khan, followed by Asaf Khan (IV) in 1614.7 He would eventually rise through the ranks to be one of Nur Jahan’s most trusted ministers, as well as the most powerful man under Shah’s reign. Additionally, despite the original tension between Nur Jahan and her stepson Shah Jahan, he was also considered a member of the junta. The group effectively controlled every aspect of the empire: the crown, the court and the provinces. Before 1611, no member of Nur Jahan’s family held a provincial governorship, but between 1611 and 1627, 12 such members did.8 During this period, coins also began to be struck in Nur Jahan’s name – Nur Jahan, the Queen Begum – demonstrating her role as sovereign to the people of the empire.9

Patronage

Throughout Nur Jahan’s reign, royal patronage was a spectacle that emphasised the crown’s generosity as well as cultural flourishment. From her charity to some 500 orphan girls who she married off well with financial aid, to her patronage of British merchants over the Portuguese, she demonstrated her wealth and opulence.10 Yet, the best examples of her patronage take form in architecture. Two prominent examples were both her father’s and her own tombs. Her father’s tomb in Agra was such a colossal project that it took six years to complete and cost around 1,350,000 rupees, of which Nur Jahan paid most of the expense.11 Her father’s tomb was so lavely completed that the whole thing was adorned with semi-precious stones: Jasper, cornelian, topaz, and onyx, and was unparalleled before or after. Similarly, Nur Jahan’s own tomb, whilst on a more modest plan, still reflected parallels to her husband’s and father’s tombs. At the time, cypresses, tulips, roses, and jasmine were planted alongside the brick pathways, canals, waterfalls, tanks, and fountains that laid out the garden. However, unlike Jahangir’s and Itimaduddaula tombs, we do not know much of Nur Jahan’s. Whilst the crown and court protected the other two, Nur Jahan’s tomb was not protected by imperial immunity from marauding bands, meaning much of her original tomb is gone, despite modern restorative practices.12

‘Though Nur Jahan be in form a woman, in the rank of men she’s a tiger-slayer.’13

However, despite her ambitions, prowess and success, Nur Jahan’s power took massive hits during the 1620s.

The death of her mother, Asmat Begum, in 1621, and her father, Itimaduddaula, in 1622, witnessed the heads of the junta structure disappear. Beneath it, the remaining bonds disintegrated, and the junta itself fell apart. And whilst Nur Jahan and her brother continued to work together, as the tides slowly moved against her, her brother started to side with Shah Jahan in secret. Additionally, after a plot by Nur Jahan to have Shah Jahan removed from power, insinuating that he a hand in the auspicious death of Khusrau.14 The tense relationship between Nur Jahan and her stepson Shah Jahan finally reached a breaking point, and fearing for his life in 1622 rebelled against his father and step mother. His rebellion would last four years before he was forced to sue for peace in 1626, after he failed to seize the throne. Nur Jahan also started to see opposition at court, with Mahabat Khan, an old and trusted friend to Jahangir, pleading with him to see sense, not understanding why he would pass sovereign powers to a woman.15 But Mahabat Khan failed to persuade Jahangir to change course, and upon Nur Jahan’s discovery of his actions, the two’s relationship never repaired.

The Fall of Nur Jahan

Fearing for his life, Mahabat Khan, between March and September 1626, rebelled against Nur Jahan. It is importatnt to note that his rebellion was not against Jahangir, as he asserted that the ill’s of the throne were a result of Nur Jahan’s bewitchment of him. Nur Jahan and her brother accused Mahabat Khan of embezzlement to undermine its efforts, but it failed to hold.16 Instead, Mahabat Khan captured Jahangir and placed him under confinement, but he missed the opportunity to capture Nur Jahan. What would follow was Nur Jahan and court officials attempting to defeat Mahabat Khan and rescue Jahangir, but the battles would end disastrously for Nur Jahan’s side. After failing to defeat Mahabat Khan and the rebellion, she was forced with no other option than to surrender. Mahabat Khan did try to have Nur Jahan murdered by convincing Jahangir to sign the papers, but he refused.17 additionally, feelings towards Mahabat Khan at court began to sour, and fled from court to join Shah. Jahangir had narrowly held on to power, but his now ailing body would fail to be prolonged, finally scumming in 1627. After a few months of a succession crisis, Shah Jahan ascended to the throne, and his once mighty stepmother, Nur Jahan, was exiled to Lahore with her daughter. She would remain there, away from the court and the centre of power, till her death in 1645.

Footnotes:

- Margaret Gaida, “Muslim Women and Science: The Search for the ‘Missing’ Actors,” Early Modern Women 11, no. 1 (2016): 203 https://www.jstor.org/stable/26431449. ↩︎

- Ellison Banks Findly, Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 47. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 40. Jahangir gave Nur Jahan two names during their marriage; the first was Nur Mahal, which meant ‘light of the palace.’ The second was Nur Jahan, which meant ‘light of the world.’ ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 31. ↩︎

- Abraham Eraly, The Mughal Throne: The Sage of India’s Great Emperors (London: Phoenix, 2004), 271. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 37. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 37. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 45. ↩︎

- Eraly, The Mughal Throne, 276. ↩︎

- Fatima Z, Bilgrami, “Economic Status Of Ladies Of The Mughal Court (Summary),” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 54 (1993): 360, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44142976; Findly, Nur Jahan, 286. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 230. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 243. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 16. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 169. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 47. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 264. ↩︎

- Findly, Nur Jahan, 289. ↩︎

For further resources, refer to the Comprehensive Bibliography.